Me and Bobby used to hang out at the railroad trestle that crossed the river between Oak Grove and Lake Oswego. We would climb the metal ladder that was attached to the cement pillar at the edge of the river, and climb off onto the 2 x 12 plank walkways that were on each level of the timber structure over the bank. I don’t know, maybe we were pirates. I don’t think so. Mostly we were just bored.

The bridge was only used a couple of times a day, hauling wood chips and sulfur to the paper mills 10 miles upstream. Sometimes we would cross over to the other side stepping tie to tie with nothing between them but a view of the water below. We always wondered what we would do if a train came while we were half way across. There was not enough room to get out of the way. It never happened though.

Bobby’s dad died when Bobby was 14. His dad was a drunk. He turned yellow and puked himself to death. Some people said he just never got over the war. I used to hull walnuts with him in the fall out on their front porch until my hands were all walnut brown. Then we’d take them up to the attic to dry among all the empty gallon Thunderbird wine bottles. He would always tell me stories about when he was a kid growing up in the hills. He never talked about the war, and no one ever asked. It was like it never happened.

He used to drive out to the potato fields and load the trunk of his car up with cull potatoes. He would always bring us a load. He was one of the nicest people I ever knew.

Everything in Bobby’s house smelled like wood smoke and bacon. It would even get into your clothes if you stayed long enough. Bobby’s Dad smoked Prince Albert pipe tobacco that he rolled up in Zig Zag papers. When his hands were steady, he did a masterful job. When they weren’t, I’d roll the tobacco for him. I wasn’t nearly as good as he was, but they worked.

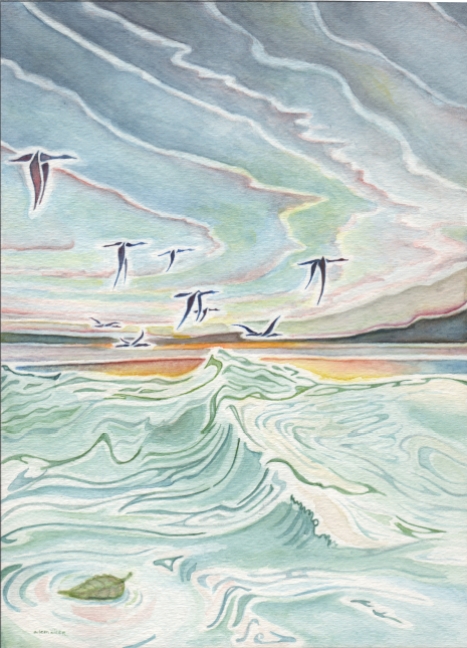

We used to stay up all night long playing games of chance, a roll of the dice, the luck of the draw, seeing the lady’s face appear, a twist of fate, a wink, a nod,- the waters rippled on down stream over the monsters hidden in the deep; and when morning came, we rode our skateboards down Molalla Avenue in the rain over soggy yellow leaves flattened on the cement, hoping to avoid the pebbles that would lead to disaster. Sometimes we would end up at the library, sometimes we would end up at the river where the paper mills were, where fishermen fished for salmon in front of the waterfalls.

Bobby wanted to be a drummer. He didn’t have any drums but he had drumsticks. I was supposed to get a guitar, and we were going to play together, but after his dad died, his mom took him off to Washington State and I never saw him again. The last I heard, he was waiting tables in Seattle.

Mountain rivers are all roar and rush. In the spring they turn milky white, and turquoise from the melting snow. When the first green starts appearing, the salmon berries with the blooming trilliums and skunk cabbages always being among the first to show themselves. There is a certain perfumed smell to the woods through which the mountain rivers run, the dampness, the dripping rain. I can smell it still, a thousand miles away in the desert. The mountain rivers, they all join hands as they leave the hills behind and become a bigger river that ships from the ocean can sail up. The river where the trestle crossed ran deep, being squeezed in by basalt on either bank. The bank that people fished from was a basalt table that dropped vertically to the river’s bottom. When the tide pushed the river back, it would rise and cover the rocks. When it rained, it would pattern the water’s surface with a myriad of expanding circles. Sometimes, at the top of the tide, the water would turn mirror smooth, and yet the current still kept the floating debris moving on downstream. Just staring out over the water sometimes would do something to you way down deep inside, and you’d shiver even if you weren’t cold.

In the fall we moved away. Dad thought he had a cheap way to get rich. That didn’t really work out too well. He wrecked the trailer house and pickup in a storm in Kansas, and the service station he bought in Missouri burned down before he could take possession, so we went to Texas in a $200 old Ford, and the clothes on our back.

The last time I was at the trestle, it was raining and the water was running high. The seagulls had flown in from the coast ahead of a storm, and were contesting a dead fish with the some local ravens.

Bobby’s dad made me a blue stocking hat when he was in rehab at the Veteran’s Hospital the year before he died. I was wearing it when I got swept off a log into the ocean by a sneaker wave, and lost it.